Inclusion and Arts

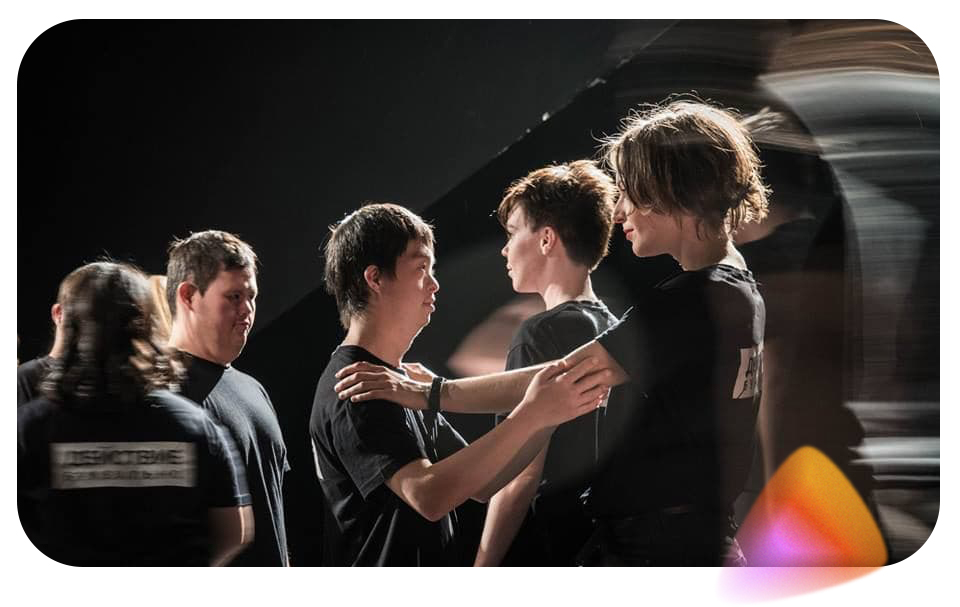

When we started working and getting to know the guys, we had a super simple exercise – to come on stage and let others to look at you. You just come and stand in front of the audience. This develops the skill of being in public, helps not to worry or to be shy. This is difficult and easy at the same time. It took our artists with developmental disabilities about a year to stop asking when they were allowed to exit.

We were told that people with autism spectrum disorders did not have imagination or interest in anything. We were told that people with Down syndrome did not have abstract thinking. That’s not even remotely true! They could not joke if they did not have imagination or abstract thinking. We laugh a lot in our theatre, and this is a remarkable indicator. Everything depends on attitude: it is important to create such an environment, where people with special needs can prove themselves.”

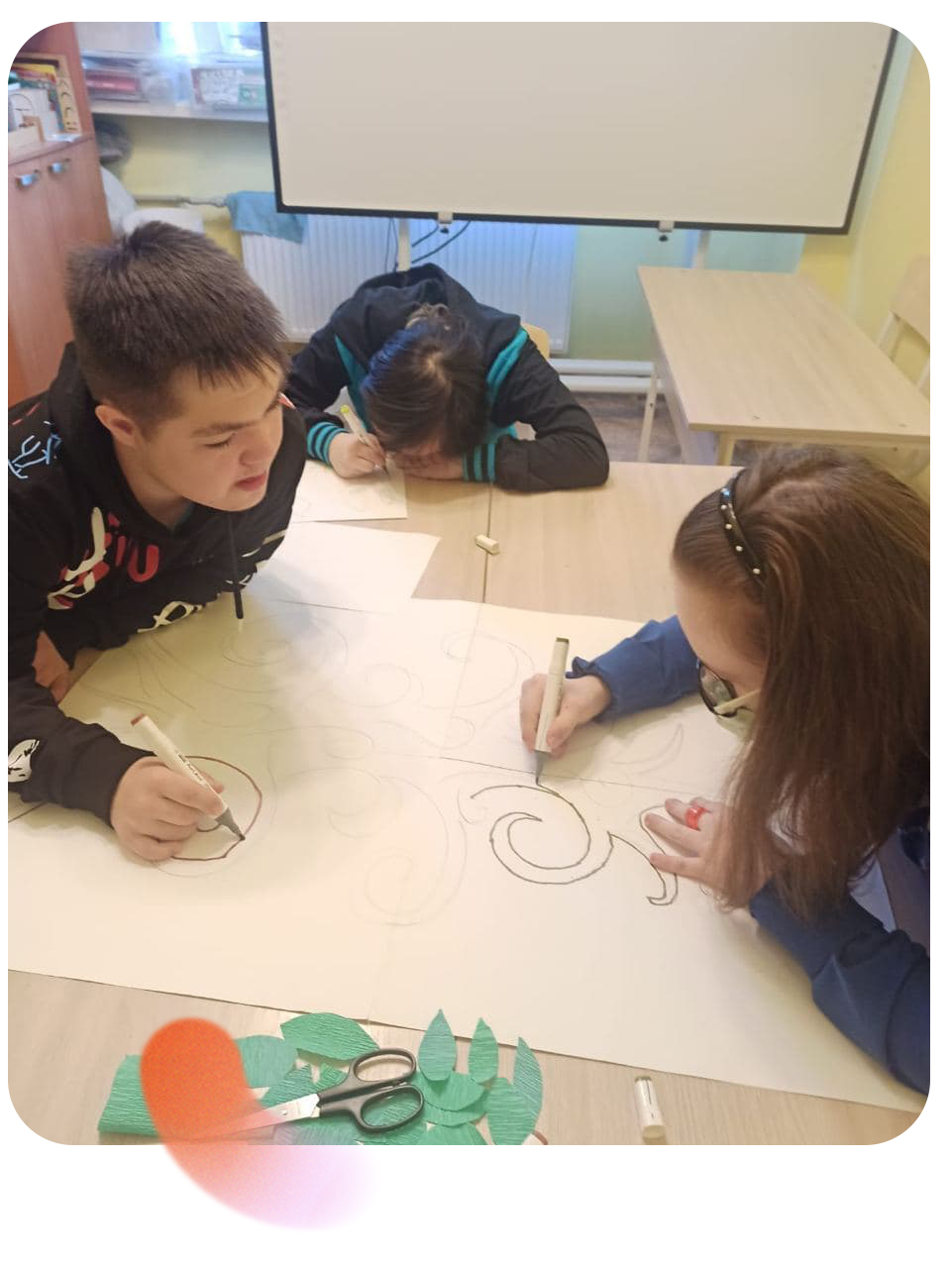

If you ask me how this all relates to theatre and why this sphere cannot be automated, I would say that it is all about a possibility of making mistakes. The thing is that mistakes are the most important and amazing element when we deal with sensory perception, such as music, fine arts and theatre.

Inclusion and Psychology

Usually it is children who mirror their parents, but when a child with special needs is born to a family, parents often start mirroring the child. If the child is hyperactive, then the parent becomes hyperactive; if the child is aggressive or hypoactive, the parent mirrors these qualities without realising it. Therefore, if parents begin to work on themselves, they help their child.

Inclusion during the Pandemic

And they may not have necessary resources. As a psychologist, I know that many parents are exhausted and burnt out, while a child resembles a battery which needs to be charged regularly.

Inclusion in Theatre and Cinema

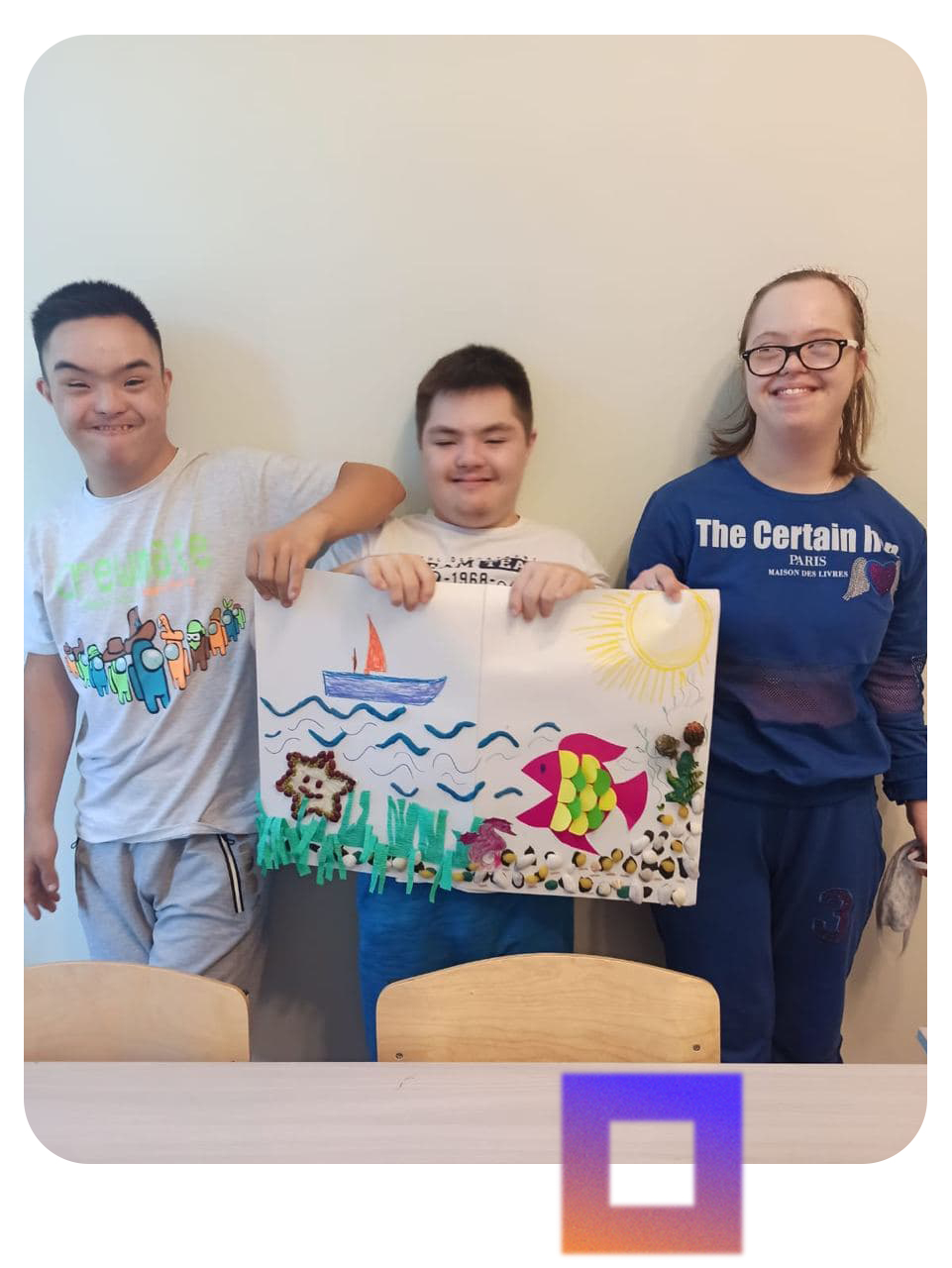

Almaz, the hero of the film, has Down syndrome. I understand that this syndrome has different forms and specifics, but I can say with confidence that Almaz and his colleagues in the Literal Action theatre are very interesting people; each of them has their own world, dreams and aspirations. Perhaps these guys have had more attention from their parents at home, had special education and have been involved in social life; this is why they feel free and liberated. In some moments I even forgot about their development disabilities, wanted to join them, went to drink coffee with them and took part in their conversations about films and artists.

The Literal Action theatre managed to create our society on a small scale: actors fall in love (I have lost count of Almaz’ ‘fiancées’), get offended and have fun, and, what is more important, they work. Almaz is proud of his work, his honestly earned money which he, like all ordinary people, spends to buy new clothes or go to cafe.

I hope this film will convince parents of children with special needs that they need not seclude them at home and stifle their individuality, will encourage parents to see their children’s passion for any job which will help them become independent, and, most importantly, to empower them to be who they are.”

Photographs were provided by heroes of an article

Данный проект реализуется с помощью гранта от Посольства США в Нур-Султане, Казахстан. Мнения, выраженные в материалах, принадлежат их авторам и не обязательно отражают точку зрения Правительства США или Дипломатической Миссии США в Казахстане.